Hyderabad, India — The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), in partnership with the Indian Council of Agricultural Research–Indian Institute of Rice Research (ICAR-IIRR), launched a five-day national training course on genomic predictions and data-driven crop breeding on 24–28 November 2025 in Hyderabad.

India Hosts Advanced Training on Genomic Predictions to Boost Rice Breeding

The training brings together 37 plant breeders, geneticists, research scholars, and early-career scientists from across the country to strengthen their skills in modern genomic tools essential for rice improvement. The program combines lectures and hands-on sessions covering quantitative genetics, statistical genomics, predictive modeling, and genomic selection. Participants are working with actual breeding datasets to learn R programming, mixed models, relationship matrices, G × E interaction analysis, and genomic prediction methodologies.

During the opening ceremony, ICAR-IIRR Director Dr. Raman Meenakshi Sundaram emphasized the importance of genomic innovations in building resilient and productive cropping systems. He highlighted the need for open-access data, collaborative research, and continuous capacity development to advance national food security objectives.

The course is led by IRRI Rice Breeding Innovation (RBI) scientists Dr. Waseem Hussain, Dr. Mahender Anumalla, and Ms. Margaret Ciar, who are guiding participants in applying genomic selection and predictive breeding tools in real-world breeding pipelines.

IRRI Senior Scientist and Regional Breeding Lead–South Asia Dr. Vikas Kumar Singh said the training reinforces the critical role of integrating genomic information with data-driven decision-making. He noted that the program equips India’s next generation of breeders to fast-track varietal development and supports IRRI’s ongoing commitment to strengthening national breeding capacity.

This year’s edition builds on earlier runs of the course first launched at IRRI Headquarters in the Philippines in 2024 and replicated at ICAR-IIRR the same year. The program has since attracted participants from Asia and Africa and is regarded as one of IRRI’s most impactful capacity development initiatives.

Participants are expected to apply genomic prediction, data-driven breeding, and optimized crossing strategies in their institutional programs following the training, contributing to India’s efforts to advance agricultural innovation and sustainability.

Interested in similar training opportunities? Visit education.irri.org to learn more or email us at irri-education@cgiar.org.

ISARC Hosts National Training on GHG Measurement to Advance Climate-Smart Rice Systems

Varanasi, India — The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) launched a five-day national training program on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in rice-based systems at its South Asia Regional Centre (ISARC) in Varanasi on 17–21 November 2025. The program aims to strengthen national capacity in accurately measuring methane emissions and identifying climate-smart mitigation strategies for rice cultivation.

Rice fields in South and Southeast Asia account for more than half of total national methane emissions, making precise monitoring essential for achieving climate targets. The training, “Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Rice Systems: Procedures and Measurement Standards,” equips participants with practical skills in field gas sampling, laboratory analysis, data evaluation, and emission calculations.

The course covers key learning areas including climate change impacts on rice production, mechanisms of GHG emissions in rice systems, IPCC-aligned inventory methods, alternate wetting and drying (AWD) mitigation practices, field setup and sampling protocols, laboratory analysis procedures, and country-specific case studies. Hands-on sessions guide participants through step-by-step measurement and reporting processes based on IRRI’s established research methodologies.

Participants represent a broad mix of public and private institutions, non-governmental organizations, and NARES partners. Institutions include the Indian Institute of Rice Research (IIRR), Kerala Agricultural University, Chaudhary Sarwan Kumar Himachal Pradesh Agricultural University, Punjab Agricultural University, Rallis India Limited, Eco Agripreneurs Pvt. Ltd., The Nature Conservancy, and RestoreEarth Solutions.

The training opened on 17 November with remarks from Dr. Anilyn D. Mannings, Head of IRRI Education, who welcomed participants, and Dr. Anthony Fulford, Soil Scientist, who addressed attendees on behalf of ISARC. Dr. Ando Radanielson, Senior Scientist and Environment and Climate Change Specialist, presented the course framework.

ISARC Director Dr. Sudhanshu Singh underscored the significance of evidence-based strategies for reducing GHG emissions in rice systems. “South Asia must lead with scientific approaches that reduce emissions while maintaining productivity. This program is a timely and impactful initiative in that direction,” he said.

IRRI Research Director Dr. Virendra Kumar, who inaugurated the program, emphasized the importance of building a collaborative community of scientists, researchers, and policymakers capable of accelerating climate action through rice-based systems.

Dr. Pratap Bhattacharya, Head of the Crop Production Division, ICAR–Central Rice Research Institute, highlighted the global importance of accurate GHG monitoring. “Scientific precision in GHG measurements is essential for shaping effective agricultural policies and mitigation strategies, not only for India but worldwide,” he stated.

Throughout the week, participants engaged in field demonstrations, laboratory work, and data interpretation exercises designed to strengthen their capacity to support national climate goals. The program reinforces IRRI and ISARC’s commitment to advancing climate-smart agriculture through rigorous research, accurate measurement, and strong institutional partnerships.

Interested in similar training opportunities? Visit education.irri.org to learn more or email us at irri-education@cgiar.org.

My Journey Toward Advancing Drought-tolerant Rice in Africa

I grew up in a farming community where agriculture shaped everyday life. The persistence of my family, most of whom were farmers, guided my academic path. Observing how climatic variability strained their efforts led me to agricultural sciences, particularly crop improvement and agronomy. From early on, I understood that rigorous science can transform traditional practices into sustainable, productive systems that protect livelihoods.

I currently serve as a Tutorial Assistant in Agricultural Botany. This role has deepened my commitment to research drought tolerance in rice because it addresses a central constraint to productivity and a central risk to household income in Africa’s rainfed and irrigated landscapes. My research interest is developing and delivering climate-resilient germplasm and agronomic packages that maintain yield even with scarce water supply, while remaining feasible for smallholders. The approach combines phenotyping for drought tolerance, geospatial targeting for variety placement, and seed system strengthening so that improved options reach both women and men equitably (International Rice Research Institute [IRRI], 2024).

This focus directly supports the Climate-resilient and Eco-friendly Rice for Africa initiative. The project advances resilient and eco-efficient rice systems through evidence-based technologies. My contribution is to connect trait discovery and on-farm validation with delivery science. In practice, this includes co-designing on-farm trials for drought-tolerant lines, linking seasonal advisories to variety of choice and planting windows, and collaborating with local multipliers so that quality seed flows efficiently to priority environments. These steps are consistent with current IRRI efforts that couple stress-tolerant rice with climate-risk mapping and targeted dissemination in Tanzania (IRRI, 2024).

The importance of this problem is evident in my national and local context. Tanzania is among Sub-Saharan Africa’s larger rice producers, with milled output reported at about 2.45 million metric tons in 2023/24 and 2.52 million metric tons projected for 2024/25. Harvested area is approximately 1.10 to 1.13 million hectares and average yields about 3.33 to 3.39 tons per hectare on a rough basis (U.S. Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service [USDA-FAS], 2025). Despite this scale, production is highly exposed to water risk. Only about 289,386 hectares were irrigated in 2019/20, which represented roughly 2.3 percent of the total planted area nationally (National Bureau of Statistics [NBS] & Office of the Chief Government Statistician [OCGS], 2021). Sector strategies note that more than 70 percent of Tanzania’s rice area is rainfed, which concentrates vulnerability to rainfall variability and dry spells (Ministry of Agriculture, 2021). Over the past three decades, the country has experienced at least six major droughts, underscoring the systemic nature of water shortages (World Bank/CIWA, 2021). These constraints periodically require market management; for example, the Government of Tanzania issued about 150,000 metric tons of rice import quotas in 2024 to stabilize supply (USDA-FAS, 2025). This means that without innovations in climate-resilient rice, food insecurity and economic vulnerability will continue to rise. Addressing this challenge through science-based solutions is, therefore, both a national priority and a personal calling.

On gender equity

Women represent about 50% of the labor force (World Bank, 2024) in rice farming, particularly in planting, weeding, harvesting, and processing, yet face time, information, and input constraints that shape farmers’ technology adoption outcomes. Recent national statistics and briefs emphasize the need for sex-disaggregated monitoring to guide equitable delivery (National Bureau of Statistics [NBS] & Office of the Chief Government Statistician [OCGS], 2024; Evans School Policy Analysis and Research [EPAR], 2020). Within CERA, I will advocate for women’s active participation in research dissemination and ensure that improved rice varieties reach them equitably. Empowering women with climate-resilient technologies can significantly uplift households and strengthen community resilience.

Women represent about 50% of the labor force (World Bank, 2024) in rice farming, particularly in planting, weeding, harvesting, and processing, yet face time, information, and input constraints that shape farmers’ technology adoption outcomes. Recent national statistics and briefs emphasize the need for sex-disaggregated monitoring to guide equitable delivery (National Bureau of Statistics [NBS] & Office of the Chief Government Statistician [OCGS], 2024; Evans School Policy Analysis and Research [EPAR], 2020). Within CERA, I will advocate for women’s active participation in research dissemination and ensure that improved rice varieties reach them equitably. Empowering women with climate-resilient technologies can significantly uplift households and strengthen community resilience.

On climate change mitigation and adaptation

Drought-tolerant rice varieties reduce the need for intensive irrigation by lowering pressure on water resources while maintaining productivity. This adaptation strategy directly improves farmers’ capacity to withstand climate shocks. Moreover, eco-friendly practices associated with such varieties as reduced fertilizer use and sustainable water management can help minimize greenhouse gas emissions, thereby contributing to mitigation efforts. Recent syntheses report substantial water savings and notable reductions in methane emissions when Alternate Wetting and Drying (AWD) is correctly implemented and monitored, often without compromising yield (Gao et al., 2024; Li et al., 2024).

As a member of this project, I expect to sharpen my skills in plant breeding, molecular biology, and eco-friendly agronomic practices, while also learning from interdisciplinary collaboration across countries and contexts. I hope to contribute not only through scientific research but also by bridging knowledge between the laboratory and farming communities. My vision is to emerge from this experience as a researcher equipped to lead innovation for climate-resilient agriculture, ensuring that smallholder farmers especially women are not left behind in the fight against climate change.

In conclusion, my academic interest in African rice drought tolerance, combined with my professional background and personal motivation, strongly aligns with the goals of the project. By addressing a pressing local and continental challenge, promoting gender equity, and advancing climate-smart innovations, I am committed to contributing meaningfully to the success of this project.

Climate-Resilient and eco-friendly rice systems in Africa: Integrating Gender Equity and Sustainable Agronomic Practices

I grew up in a small district called Maswa, situated in the northern part of Tanzania, south-east of Lake Victoria. I was raised by my mother. She was a nurse but also a smallholder farmer. She cultivated rice and maize at our farm located around our home. Just like other smallholder farmers, my mother faced many challenges, such as unpredictable weather patterns, use of old, traditional varieties, limited access to inputs, and poor local soil knowledge. Growing up with my mother exposed me to the most traditional ways of cultivating rice and the challenges they faced. The whole experience basically drove my desire to one day become an agricultural researcher; hence, I chose to pursue a BSc in Agronomy.

I grew up in a small district called Maswa, situated in the northern part of Tanzania, south-east of Lake Victoria. I was raised by my mother. She was a nurse but also a smallholder farmer. She cultivated rice and maize at our farm located around our home. Just like other smallholder farmers, my mother faced many challenges, such as unpredictable weather patterns, use of old, traditional varieties, limited access to inputs, and poor local soil knowledge. Growing up with my mother exposed me to the most traditional ways of cultivating rice and the challenges they faced. The whole experience basically drove my desire to one day become an agricultural researcher; hence, I chose to pursue a BSc in Agronomy.

I got employed as a Junior Agronomist at a coffee producing company called Ngila Estate Ltd., situated in Tanzania’s Karatu district. I worked under the principles of climate-smart agriculture and was presented with a certification by the Rainforest Alliance. I also worked in the Department of Pest Scouting and Control. As an agronomist, I practically performed soil sampling for pH and nutrient analysis and recommended the best ways to solve pH and nutrient imbalances. I did research based on the effectiveness of biochar as a soil amendment and the effectiveness of local lime sulphur on treating leaf rust and coffee berry disease.

As a Climate-resilient and Eco-friendly Rice for Africa (CERA) Master’s student, my study area is focused on climate adaptation objectives using agronomic technologies. It addresses the urgent challenge of sustaining rice production in drought-prone areas.

Rice is the second most important commercial and food crop in Tanzania after maize. More than 18% of households rely on rice as a staple, and the sector provides livelihoods for over 2 million smallholder farmers (URT, 2020). Tanzania is the second largest producer of rice in Southern Africa after Madagascar, with a production level of 818,000 tons (JICA 2007). However, Tanzanian rice productivity is lower than most of its neighboring countries and one of the weakest in the world (European Union, 2010). About 71% of the rice in Tanzania is produced under rainfed conditions, while irrigated land accounts for 29% of the total, with most of it in small village-level traditional irrigations, making it highly vulnerable to drought and erratic rainfall. Studies indicate drought stress can reduce yields by 40–60%, particularly in semi-arid regions such as Shinyanga, Dodoma, and Morogoro (AfricaRice, 2021). Paddy rice cultivation is one of the most important sources of anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs), mainly nitrous oxide (N2O), methane (CH4), and carbon dioxide (CO2) (IPCC 2014; Arunrat et al., 2018), and is the major driving force for climate change (Smith et al., 2014).

This makes the problem statement highly significant in the national context. Thus by promoting various agronomic strategies like water management practices, particularly promoting intermittent drainage and alternate wetting and drying (AWD) (Minamikawa and Yagi, 2009), system of rice intensification (SRI) (Gathorne et al., 2013), improving organic management by composting, using rice cultivars with few unproductive tillers, high root oxidative activity, and high harvest index (Zheng et al., 2014), application of fermented manure like biogas slurry (Petersen, 2018), incorporation of biochar and adopting direct-seeding of rice (DSR) (Susilawati et al., 2019) will contribute to closing Tanzania’s rice yield gap, improving resilience in smallholder systems, mitigating GHGs and supporting national strategies for climate adaptation and food self-sufficiency.

As a member of the project, I intend to contribute by addressing gender equity and climate change challenges. Women provide more than half of the labor in rice farming in Tanzania, yet they face barriers to resources and training. By ensuring their active involvement in agronomic research and farmer training and promoting labor-saving, climate-smart technologies, I aim to reduce gender gaps and empower women farmers economically and socially.

On climate change, my focus is on promoting adaptation strategies such as drought-tolerant varieties, water-saving irrigation methods, and soil fertility management to safeguard yields in drought-prone regions. I will also emphasize mitigation practices, including eco-friendly soil amendments, biochar, conservation tillage, and reduced reliance on synthetic fertilizers, which can lower greenhouse gas emissions. These contributions will help build inclusive, resilient, and sustainable rice systems that align with national food security and climate goals.

I expect to enhance my knowledge and skills in climate-smart and eco-friendly rice production, particularly in developing practical solutions for drought-prone areas. I look forward to contributing to scientific innovation through agronomic research and sharing findings that address yield gaps and strengthen resilience in rice systems. I also expect to promote gender equity by ensuring women farmers actively engage in training and decision-making, thereby supporting inclusive development.

I expect to enhance my knowledge and skills in climate-smart and eco-friendly rice production, particularly in developing practical solutions for drought-prone areas. I look forward to contributing to scientific innovation through agronomic research and sharing findings that address yield gaps and strengthen resilience in rice systems. I also expect to promote gender equity by ensuring women farmers actively engage in training and decision-making, thereby supporting inclusive development.

Through this project, I hope to strengthen collaboration with researchers, policymakers, and farmers across Africa, expanding my professional network and exposure to diverse expertise. I also expect to gain experience in climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies, as well as in farmer capacity building. Ultimately, I aspire to align my contributions with Tanzania’s food security priorities and Africa’s broader climate-smart agriculture goals, ensuring sustainable and impactful outcomes.

I am truly grateful for the opportunity to be selected as part of the Climate-Resilient and Eco-Friendly Rice for Africa project. This scholarship is both an honor and a responsibility, and I am committed to contributing meaningfully toward its goals of food security, climate resilience, and gender equity. I look forward to learning, collaborating, and applying my skills to support sustainable rice systems in Tanzania and across Africa. My sincere thanks go to the project team and sponsors for this trust.

International Day of Rural Women

Driving Change Through Research: Empowering Rice Farmers Amid Drought

Growing up in Tanzania, pilau was always a dish of joy in my family, fragrant rice filled with spices and shared at gatherings. Every plate carried more than flavour; it carried the story of the farmers who work tirelessly in the fields. Over time, I became more aware of the fragility of their livelihoods. Droughts, unpredictable rainfall, and declining soil fertility often reduce their harvests. What concerned me most was the reality that these challenges do not affect everyone equally. Women, landless farmers, and other vulnerable groups are often excluded from resources and decision-making, making them more exposed to climate shocks. Witnessing these inequities shaped my research interest: exploring how fairness is addressed in drought adaptation strategies and how these strategies impact the most vulnerable rice farmers.

My academic path reflects this passion. I began with a degree in Actuarial Statistics, which allowed me to analyze complex data and understand patterns. I am now pursuing a master’s in project management and Evaluation, which equips me to design, monitor, and assess development projects. Together, these skills enable me to ask critical questions about adaptation: who benefits, who is left out, and how these choices shape the future of farming communities.

Rice is central to Tanzania’s food system and daily life. It is the second most important crop after maize and a staple for millions of households. In the 2022/23 season, farmers harvested over one million hectares of rice, producing about 2.4 million tons. Average yields were only 2.2 tons per hectare, although this varied from less than one tonne in some regions to more than four tons in the best performing areas (Discover Agriculture, 2025). There has been some progress. For example, under the TANRICE2 programme, yields rose by 40 percent in seven years, from 3.2 to 4.5 tons per hectare (The Citizen, 2020). Yet many farmers, especially those relying on rainfed systems, still use traditional varieties that yield only 1.5 to 2.5 tonnes per hectare and are highly vulnerable to drought (IRRI, 2024). When climate shocks strike, these households are left with little income, food insecurity, and fewer options to recover. The burden is not shared equally. A study in Mbarali District found that 78 percent of men participated in multiple rice production tasks compared to only 49 percent of women. A larger proportion of women were confined to low participation roles, while very few reached high participation levels (FAO, 2021). This shows how unequal access to land, credit, and decision-making limits women’s ability to benefit from rice farming, even though they are central to production.

As a CERA scholar, I aim to place equity at the heart of climate adaptation strategies. I will focus on making the barriers women face in accessing irrigation, drought-tolerant seeds, and climate information visible. Highlighting these disparities allows us to design strategies that enable women to participate fully and share fairly in the benefits of climate-smart rice farming. When women thrive, entire households and communities become more resilient. On climate change adaptation and mitigation, I study how different farmer groups adopt practices such as improved water management, soil conservation, and new rice varieties. I am interested in how these innovations are distributed, because leaving the most vulnerable behind weakens overall resilience. Many of these practices also contribute to mitigation by promoting resource efficient and environmentally friendly farming methods.

Being part of the CERA project is both a professional step and a personal commitment. I look forward to learning from the scientists at IRRI, working alongside fellow scholars, and engaging with rice farming communities to understand their lived experiences. I want to strengthen my ability to translate research into practical recommendations that can influence policy and practice. Most importantly, I hope to ensure that the benefits of climate-smart rice production reach those often excluded, especially women and marginalised groups.

I imagine a future where rice farming in Africa is resilient, fair, and environmentally sustainable. A future where farmers, regardless of gender or status, are equipped not just to survive climate shocks but to thrive. A future where every grain of rice, whether in pilau at a celebration or in a simple family meal, reflects resilience, fairness, and dignity. For me, being a CERA scholar is not simply about academic achievement. It is a pledge to champion equity, sustainability, and a better future for farmers in Tanzania and across Africa.

Towards Achieving Equitable and Climate-Resilient Rice Farming in Africa

I was raised in Ruvuma, a region in southern Tanzania, where my mother has been cultivating maize on our family farm, located 22 km from our home. Like many women farmers in East Africa, she faced recurring challenges from unpredictable rainfall and limited access to reliable weather information. Most of the time, she relied on indigenous knowledge to decide when to plant a practice that, given today’s shifting climate patterns, often felt like a gamble. These uncertainties frequently result in low yields and unstable household income. Witnessing her navigate these struggles inspired me to pursue a career in agricultural research, with a strong focus on climate change adaptation and rural livelihoods.

Over the past two years, I have been privileged to contribute to regional projects such as Enhancing Climate Resilience in East Africa (ECREA) and Building Equitable Climate-Resilient African Bean and Insect Vectors (BRAINS). Both initiatives underscored the critical role of ensuring that women, youth, and persons with disabilities have timely access to weather and climate information. Through this work, I witnessed how empowering vulnerable groups with knowledge strengthens decision-making, improves resilience, and ensures that they benefit more equitably from agricultural innovations. These experiences taught me that while technologies and improved practices are essential, true transformation in African agriculture also requires addressing inequities that prevent women and youth from realizing their full potential.

As a Climate-smart and Eco-friendly Rice for Africa (CERA) PhD scholar, my study will focus on strengthening the resilience and inclusivity of rice farming systems in East Africa. Specifically, I am interested in understanding how inequities within the rice value chain, particularly those affecting gender groups (with special lens of women farmers), shape the adoption of climate-smart practices and influence household livelihood outcomes. This aligns closely with the CERA project’s vision of promoting climate-resilient, eco-friendly, and socially just rice systems in Africa.

Rice is central to food security in Tanzania and Kenya. In Tanzania, rice accounts for about 17–21% of total grain or cereal production and is cultivated by over one million households, making it central to both food security and income generation (Lyanga, 2025). Extreme climate events, including droughts and floods, significantly reduce rice yields in Tanzania like any other country in our region and globe at large. Studies show that such events can cause yield losses ranging from 25% to over 70% in severe cases, with some Tanzanian floodplain farmers reporting losses of 50–100% during extreme floods (Mwakyusa et al., 2023; Akpa, 2024). Tackling these challenges is more than about productivity; it is about reducing vulnerability and promoting equity along rice value chains. My work aligns with CERA’s goals by exploring climate-smart practices that build resilience while promoting sustainable, low-emission rice systems.

I will actively engage women-led households and youth groups in rice-farming communities, for co-developing participatory approaches that reflect their realities. This will not only strengthen inclusivity but also ensure that the isolated groups’ voices shape the design and adoption of adaptation strategies.

Under CERA’s climate change mitigation and adaptation goals, my research will analyze how different climate-smart rice practices perform under variable conditions, considering both costs and benefits along rice value chains. By generating evidence on which practices are most effective and feasible for smallholders, I hope to inform strategies that are value chain node specific that reduce climate risks while supporting the sustainability of actors regardless of their gender groups and other socioeconomic aspects.

Contextualization of the study

The agriculture sector in Tanzania employs about 65% of the population, with rice also identified as a strategic crop for national and regional food security (Basungu, 2023). Yet gender groups like women farmers face systemic barriers: less than 20% of women own land, and fewer than 15% have access to formal credit (Awoke et al., 2025). At the same time, rice yields average just 2.2 tons per hectare, far below the potential of 6–7 tons under improved management (Kwesiga et al., 2020; Mboyerwa et al., 2022). Bridging these gaps requires not only technical innovations but also institutional reforms that ensure these gender groups, like women and youth, can actively participate and benefit in the face of climate-related risks.

The agriculture sector in Tanzania employs about 65% of the population, with rice also identified as a strategic crop for national and regional food security (Basungu, 2023). Yet gender groups like women farmers face systemic barriers: less than 20% of women own land, and fewer than 15% have access to formal credit (Awoke et al., 2025). At the same time, rice yields average just 2.2 tons per hectare, far below the potential of 6–7 tons under improved management (Kwesiga et al., 2020; Mboyerwa et al., 2022). Bridging these gaps requires not only technical innovations but also institutional reforms that ensure these gender groups, like women and youth, can actively participate and benefit in the face of climate-related risks.

In regions which experience extreme weather phenomenon such as Morogoro in Tanzania and Mwea in Kenya, the stakes are even higher. Farmers in these areas are already grappling with shorter and less predictable rainy seasons, sudden floods, and rising production costs. Without deliberate action, these challenges threaten not only household welfare but also national food security. Addressing them requires climate-smart and gender-responsive solutions that enable farmers, especially women, to adapt, build resilience, and sustain their livelihoods.

Finally, as an ambitious CERA scholar, receiving this scholarship is both a personal milestone and a responsibility. I look forward to engaging deeply with rice smallholder farmers, particularly different gender groups of weather-extreme regions areas of Tanzania and Kenya and learning from their lived experiences. In working with CERA’s diverse network of partners, I also see this as an opportunity to grow into a researcher and/or academician who can bridge science and community realities, by disseminating the contextualized research findings, hence making rice systems not only climate-resilient but also socially just and equitable.

ISARC Hosts Advanced Training on Soil Health Management in Rice-Based Cropping Systems

Varanasi, 20 September 2025: The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), South Asia Regional Centre (ISARC), Varanasi, in collaboration with IRRI Education, has successfully concluded a four-day advanced training program from 17 September to 20 September 2025 on “Advanced Approaches to Soil Health Management in South Asia’s Rice-Based Cropping Systems.”

The program brought together participants from leading agricultural universities and ICAR institutes, including ICAR-IISS Bhopal, ICAR-IIFSR Modipuram, BHU-Varanasi, SHUATS Prayagraj, Punjab Agricultural University, and others. Renowned experts from BHU, ICAR-NBAIM, ICAR-IARI, IFDC, and ISARC contributed as resource persons.

Speaking at the inauguration, Dr. Sudhanshu Singh, Director of ISARC, remarked that soil is the foundation of our food systems. Through this program, IRRI is building regional expertise and preparing the next generation of professionals to safeguard soil health for sustainable food security.

Unlike routine training courses, this program was designed as an in-depth, blended learning experience that combined lectures, hands-on activities, field visits, and laboratory demonstrations. Key sessions included digital tools for soil and crop management, where ISARC soil scientists Dr. Anthony Fulford and Dr. Ajay Mishra led sessions on the Rice Crop Manager (RCM), a farmer-friendly decision-support tool designed to optimize nutrient use efficiency and enhance productivity in rice-based systems.

Participants also explored the scope of soil spectroscopy for rapid and cost-effective soil analysis, with demonstrations at ISARC’s advanced laboratory highlighting its potential to support farmers with timely and precise soil health information and offering scalable solutions for better nutrient management.

A session on soil health governance and policy, delivered by Dr. Yashpal Sahrawat, Director-Resilience and Environment at the International Fertilizer Development Center (IFDC), USA, emphasized the importance of policy frameworks and governance mechanisms such as the Bharat Soil Health Policy, with a timeline of phased implementation by 2047. This session included discussions on institutional support for promoting sustainable soil health practices at both national and regional levels, and called for low-cost, incentivized soil health policy.

In addition to classroom sessions, participants engaged in exposure visits to progressive farmers’ fields in Varanasi, where they observed integrated soil and water management practices in real-world settings. They also worked with soil health kits and conducted lab-based analyses to strengthen their technical expertise.

By combining scientific insights, digital innovations, and policy perspectives, the training equipped soil scientists, agronomists, extension professionals, and faculty members with actionable knowledge and practical skills to advance climate-smart, farmer-centric soil health management strategies across South Asia.

Interested in similar training opportunities? Visit education.irri.org to learn more or email us at irri-education@cgiar.org.

Proving impact: IRRI equips professionals to achieve measurable results

Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines (11 July 2025) — Measurable impacts are essential in policy and program development to achieve transparency and accountability. Impact evaluation plays a crucial role in determining whether a particular intervention has made a difference.

This was the core focus of IRRI’s Workshop on Impact Evaluation and Causal Inference held from 8 to 11 July 2025 in IRRI’s Headquarters. This four-day training equipped participants with tools to assess the effectiveness of interventions. Impact evaluation focuses not only on outcomes but also on attribution, whether the observed changes in target key indicators can be confidently linked to the intervention itself. This approach helps guide decisions on which programs should be scaled, redesigned, or discontinued. The course addressed a key challenge faced by development professionals: how to generate credible evidence about what works, why it works, and at what cost.

In her opening remarks, Dr. Anilyn Maningas, Head of IRRI Education, underscored the training’s relevance across sectors. She noted that in a complex and resource-constrained environment, it is more critical than ever to understand what works and why. “This workshop aims to equip you with the tools and frameworks necessary to answer these pressing questions using rigorous evaluation methods and causal inference techniques,” she said.

This call for evidence-based action was echoed by Dr. Patrick S. Ward, Associate Professor at the University of Florida. He explained that decision-makers often face several competing policy options, and that selecting a course of action should be based not on ideology or anecdote, but on strong and credible evidence. Grounding policies in well-designed impact evaluations, he added, is essential to making informed and effective choices.

A key component of the training was the Theory of Change, a tool that helps map out how and why an intervention is expected to produce desired results. Participants learned how this framework can clarify assumptions, identify relevant indicators, and support the design of high-quality, policy-relevant evaluations.

Trainees were also introduced to designing, implementing, and analyzing randomized controlled trials, and quasi-experimental methods such as difference-in-differences (DiD), instrumental variables (IV), and regression discontinuity designs (RDD). These rigorous impact assessment methods help strengthen the credibility of evaluation findings by isolating causal effects.

Adding a practical lens, Dr. Gregmar Galinato, Professor at Washington State University, used case studies to demonstrate how to evaluate the suitability of various quasi-experimental methods.

Meanwhile, Prof. Suzette Pedroso Galinato, Associate Professor and Extension Specialist at Washington State University Extension, emphasized the importance of evaluating interventions from the standpoint of those most affected: the farmers. She shared, “Economics is like a ribbon that ties the project together. Because after all the field activities, data collection, and information dissemination, the main concern of the growers is how the intervention affects their farm environment.” Therefore, understanding the tangible impact of interventions is key to designing meaningful and responsive programs. Prof. Galinato also discussed how to determine whether the intervention introduced to the target beneficiaries is more cost-effective than other alternatives by conducting cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analyses.

The workshop serves as a timely and relevant initiative as IRRI introduced its 2025 to 2030 Strategy, which emphasizes measurable impact, evidence-informed action, and results that benefit farmers, communities, and food systems. Building on the success of this pilot run, the team plans to offer the course again next year to reach a broader group of professionals working to improve agricultural development outcomes.

Interested in similar training opportunities? Visit education.irri.org to learn more or email us at irri-education@cgiar.org.

RR2P 2025: Connecting Global Perspectives with Ground-Level Realities in Rice Science

The Rice: Research to Production (RR2P) course returned in 2025 for its 18th run, reaffirming its commitment to immersive, hands-on learning that bridges the gap between science and practice. This year’s edition brought together a diverse cohort to study rice research and production at IRRI’s Headquarters. For three weeks, participants explored the entire rice value chain through lectures, laboratory and field activities, and community engagement.

Among the participants were Yvonne Njoki Ndaru from Kenya and Jongho Bae from South Korea. Sponsored by the IRRI-DANIDA project in Africa and the Global Rice Research Foundation (GRRF) respectively, both scholars entered the program with unique academic backgrounds and motivations. Yvonne is currently pursuing a PhD in Environmental Science at Chuka University, with her research centered on how watering regimes and crop establishment methods affect greenhouse gas emissions in rice fields. Jongho, a Master’s student in Agricultural Economics at Purdue University, focuses on the role of rice trade in national food security and its implications for global inequality.

Despite coming from different disciplines, both participants were connected by a shared desire to make agriculture more inclusive, resilient, and sustainable.

An Eye-Opening Start

For Jongho, joining RR2P was a step toward bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and the day-to-day realities of farmers. “I wanted to better understand how agriculture actually works on the ground, and what challenges farmers face in their daily lives,” he said. As someone who had primarily studied agricultural trade and policy, RR2P offered an opportunity to explore the scientific and practical aspects of rice production that he had not previously encountered.

Yvonne, meanwhile, had long admired IRRI’s work and viewed the program as a vital step in her journey as a researcher. “The program’s emphasis on combining rigorous academic learning with real-world field experience immediately resonated with me,” she noted. At the start of the program, she felt a mix of excitement and nervousness, especially upon seeing participants from various countries and disciplines. “This diversity created an incredibly rich learning environment right from the start,” she added.

Learning by Doing

RR2P stands out for its strong emphasis on experiential learning. Participants were not just learning theories in a classroom; they were out in the field, engaging directly with the systems, practices, and people that define rice research and production.

Yvonne, whose work focuses on greenhouse gas emissions in rice fields, appreciated the depth and scope of the technical sessions. She found the hands-on disease and pest diagnostics particularly useful and was inspired by sessions on plant breeding. “Learning about breeding and Rapid Generation Advancement was especially meaningful. I had always admired plant breeders, and until this program, I had no experience in that area. However, by the end of RR2P, I felt empowered and well-versed in breeding practice,” she shared.

For Jongho, the course offered an in-depth look at the science behind the crop he had previously only studied through policy and trade data. The sessions on seed systems, soil management, and pest control were unfamiliar at first, but these sparked a strong interest. “These topics, though technical, were the building blocks of rice production, and I realized how essential they are to understanding the crop in its full complexity,” he said.

Both found that field visits brought technical knowledge to life. The combination of classroom and field-based learning helped them connect scientific insights with the on-the-ground experiences of farmers, a connection that will help continue shaping their work moving forward.

Ground-Level Realities

One of the most defining experiences for both Yvonne and Jongho was the visit to farming communities in Victoria, Laguna, and the Banaue Rice Terraces. For Jongho, a conversation with a local rice farmer in Victoria left an impact. “He had achieved a good harvest, but what he shared with me was far from encouraging,” Jongho recalled. “Despite producing quality rice, he explained that he often had to sell it at extremely low prices. The reason wasn’t poor demand or weather—it was a lack of access to post-harvest facilities like drying and milling. Without those, farmers are forced to sell immediately to middlemen, who take most of the profit.”

Further, that moment changed the way Jongho viewed his own field. “I saw that behind every trend or statistic are real people—whose livelihoods are often affected by infrastructure gaps and limited access to value chains. It was a clear and personal reminder that research must be grounded in the real challenges people face. That single exchange helped reframe the way I see the role of policy and economics—not as abstract forces, but as tools that can either exclude or empower.”

On the other hand, Yvonne described the rice planting activity in the IRRI experimental fields as a powerful turning point. “As we stepped into the muddy paddies, I felt an immediate connection with the farmers who perform this labor daily,” she reflected. Afterwards, she spoke with farmers in Victoria, Laguna and Banaue. “They shared their experiences, challenges, and hopes for better yields. Understanding their daily realities and linking them with the planting experience underscored the need for research that is not only scientifically sound but also adaptable to local contexts. It reminded me that innovation must be driven by farmers’ lived experiences, not abstract theories, if we truly want to achieve sustainable outcomes.”

Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration

The diversity of the course’s cohort also led to dynamic exchanges of ideas. Yvonne recalled a group discussion where participants debated solutions to food insecurity and climate change. While some advocated for early-maturing rice varieties, others emphasized sustainable farming practices. The exchange, she said, revealed the potential of combining technical and environmental approaches to address complex problems.

Similarly, Jongho worked on a project focused on salinity in Vietnam. While his group members explored breeding salt-tolerant varieties, he emphasized the importance of ensuring that innovations translate into economic benefits for farmers. “Future agricultural solutions will require close collaboration between economists and scientists. Real progress depends on our ability to listen to one another, bridge perspectives, and work toward shared goals,” he said.

Growth Through Challenge

Both participants acknowledged the demanding pace and intensity of RR2P. Jongho initially struggled with the rural environment and unfamiliar routines. Yet over time, these challenges helped him grow. “I became more grounded in how I see my role as a researcher,” he shared.

Yvonne also found the schedule packed, but she faced the challenge with resilience and curiosity. “Whenever I encountered a concept, I couldn’t immediately grasp, I made it a point to delve deeper through additional research,” she said. The supportive community of peers and mentors made the learning process both rigorous and rewarding.

Looking Ahead

As they return to their home institutions, Yvonne and Jongho carry forward not only new knowledge but also a renewed sense of purpose. Yvonne plans to collaborate with researchers and farmers in Kenya to develop context-specific, sustainable practices. Jongho, on the other hand, intends to integrate the lessons from RR2P into his work on agricultural policy and trade, ensuring that his research remains grounded in the real challenges that communities face.

Their stories reflect the spirit of RR2P, a program that brings together aspiring changemakers and empowers them to influence a more inclusive, resilient, and sustainable future for the rice-based agri-food sector.

Through the continued support of partners like the IRRI-Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA) project and the Global Rice Research Foundation (GRRF), programs like RR2P remain accessible to the next generation of leaders in rice science. While the 2025 edition may have concluded, its lessons will continue to shape the personal and professional journeys of those who took part.

As Yvonne shared, “RR2P is a journey of discovery, collaboration, and impact, where science meets practice to shape the future of rice research and sustainable farming.”

While Jongho and Yvonne’s reflections offer a glimpse into the impact of the course, they were just two of many. The 2025 RR2P cohort included professionals with backgrounds ranging from agronomy and plant breeding to agricultural economics and development. Coming from institutions such as the University of California Davis, Yunnan Agricultural University, Purdue University, Chuka University, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, National Institute for Agrarian and Veterinary Research (INIAV) in Portugal, and the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), the group brought together a rich mix of experiences that enabled interactive discussions, cross-cultural exchanges, and shared learning, connections that they are now carrying into their own work.

Interested in joining this journey? Be part of the next RR2P cohort and gain the knowledge, skills, and perspective needed to make meaningful contributions to global rice systems. The program also welcomes support for participants who may need assistance to take part. Visit education.irri.org to learn more or email us at irri-education@cgiar.org.

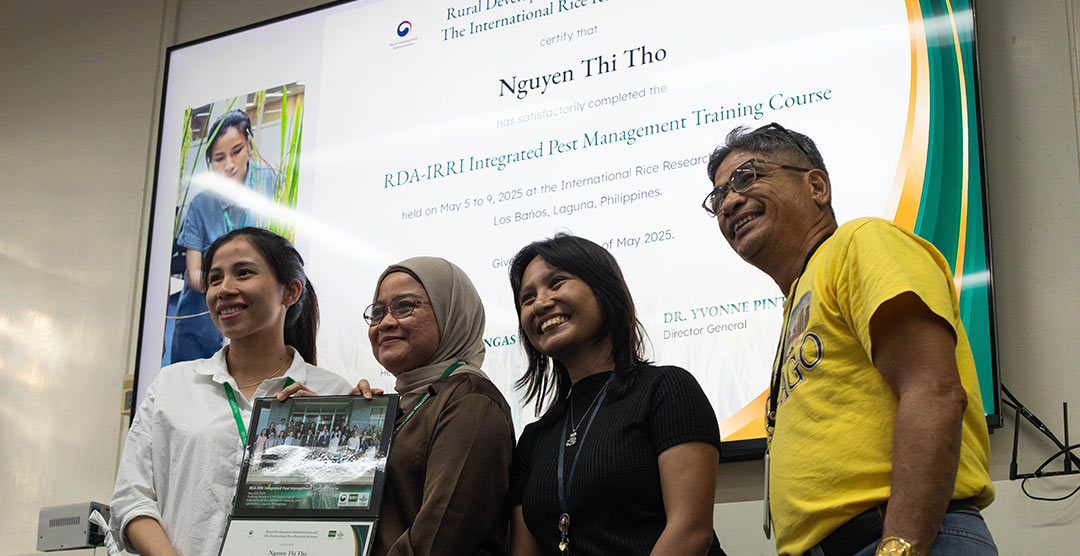

RDA-IRRI champions climate-smart pest management for sustainable rice production

LAGUNA, Philippines (13 May 2025) — IRRI emphasizes prevention and suppression at the recent International Technology Cooperation Center of the Rural Development Administration – Korea (ITCC- RDA) and IRRI training on Integrated Pest Management (IPM). The 5-day training course aimed to introduce recent paradigm shifts in rice pest management, update participants on recent advances in management technologies, and assist them in the preparation and implementation of their localized IPM research plans.

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is a sustainable and effective management approach to controlling pests in agriculture by implementing a combination of scientific techniques and ecological knowledge such as pest biology and behavior. IPM was first introduced in the 1970’s to address the growing negative effects of pesticides in agriculture. “Rice will have to be produced, processed, and marketed in a more sustainable way.”, IRRI Scientist and Country Representative for Cambodia Dr. Nurmi Pangesti said as she explained how climate change is shaping ecosystems involved in global rice production.

IPM does not aim to eliminate all pests present in the field. Rather, its goal is to control the pest population by ensuring that a single species is not dominating the ecosystem and causing significant damage to the crops. A major principle that Dr. Nurmi highlighted is that IPM emphasizes prevention and suppression of pest population before intervening through the application of chemical pesticides. IPM deprioritizes the use of chemical pesticides since they contribute to climate change. Moreover, there is a declining number of approved active substances which increases the risk of resistance development.

IRRI Senior Associate Scientist Dr. Nancy Castilla stated that climate change significantly influences the population of pests and the intensity of diseases and pest injury . “Rice yields decline by 10% for every 1-degree Celsius increase in minimum temperature.”, Dr. Castilla explained. “There is an increasing number of studies which show that the increase in crop losses to insect pests is caused by an increase in temperature by the warming climate.”

To help smallholder farmers adapt to climate change, IRRI is promoting climate-smart pest management (CSPM) which takes into consideration both integrated pest management techniques and climate change adaptation and mitigation practices. CSPM aims to reduce crop losses caused by pests, increase incomes of those farmers who practice sustainable farming, and improve overall environmental resilience.

Senior Agriculturist Russ-Uzi Mayenne A. Ebora from the Philippines Bureau of Plant and Industry (BPI) shared how the country is scaling CSPM at the community-level. She stated that they are promoting the use of biological control agents (BCAs) like Trichogramma to control the population of the destructive Yellow Stem Borers (YSB) in rice. There is a need for strong policy and investment support for scaling IPM to ensure stable supplies of BCAs for smallholder farmers.

CHECK OUT the IRRI Education website for more training and scholarship opportunities.

IRRI pioneers modern crop breeding strategy, trains researchers on One IRRI Rice Breeding Strategy and hybrid rice breeding

LOS BAÑOS, Philippines (05 May 2025) — The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), through IRRI Education, successfully concluded its Recent Advances in Hybrid Rice Breeding Training Course, which was held from 24 April to 5 May 2025 at IRRI’s headquarters in Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines. The 12-day course gathered researchers from across the globe to enhance their skills in hybrid rice breeding and contribute to the broader global food security goals.

Dr. Anilyn Maningas, Head of IRRI Education, underscored the urgency of the institute’s mission on tackling food security by transforming rice-based agri-food systems, “With global rice production needing a drastic increase despite decreasing resources such as land, water, and labor, our mission is more urgent than ever. Take full advantage of this opportunity not only to deepen your technical skills but also to build a network of peers and mentors who are equally passionate about hybrid rice breeding.”

The participants were introduced to the One IRRI Rice Breeding Strategy and its role in global rice breeding. Compared to traditional, fragmented breeding efforts, this strategy aims to unify efforts by setting standards and efficient resource management among local and international partners. Basically, this will speed up the breeding process of nutritious and market-preferred rice varieties which are also climate-resilient. This crop breeding strategy can also be replicated in similar crops. Dr. Jauhar Ali, Principal Scientist and Hybrid Rice Breeder at IRRI, served as one of the lead instructors. “How do we produce more from less? This is the challenge we face,” he said. “We need to increase production while reducing inputs like fertilizers and pesticides.” Dr. Ali emphasized the potential of hybrid rice to improve resource use efficiency and equip researchers to address global food security challenges more sustainably. Hybrid rice is a type of rice which is produced from two genetically different parents which commonly result in higher yielding varieties.

The participants were introduced to the One IRRI Rice Breeding Strategy and its role in global rice breeding. Compared to traditional, fragmented breeding efforts, this strategy aims to unify efforts by setting standards and efficient resource management among local and international partners. Basically, this will speed up the breeding process of nutritious and market-preferred rice varieties which are also climate-resilient. This crop breeding strategy can also be replicated in similar crops. Dr. Jauhar Ali, Principal Scientist and Hybrid Rice Breeder at IRRI, served as one of the lead instructors. “How do we produce more from less? This is the challenge we face,” he said. “We need to increase production while reducing inputs like fertilizers and pesticides.” Dr. Ali emphasized the potential of hybrid rice to improve resource use efficiency and equip researchers to address global food security challenges more sustainably. Hybrid rice is a type of rice which is produced from two genetically different parents which commonly result in higher yielding varieties.

Complementing this perspective, Dr. Waseem Hussain, Senior Scientist for Plant Breeding at IRRI, highlighted the role of innovation in modern rice breeding. “This course offers a comprehensive platform to understand the complete hybrid rice pipeline, from selecting parental lines to using genomic tools and digital technologies,” he said. “It’s essential that researchers see how these innovations are applied in real field conditions.”

Designed to offer a holistic learning experience, the training combined classroom lectures, hands-on laboratory sessions, and field activities. Participants engaged with a wide range of topics, including genomic selection, rice hybridization, and the application of advanced tools such as drone phenotyping and artificial intelligence in agriculture.

Throughout the course, participants interacted directly with IRRI scientists and accessed the institute’s world-class research facilities. Field activities allowed them to observe hybrid rice cultivation firsthand and apply new techniques in real-world settings.

The training concluded with positive feedback from participants, who praised the course’s high-quality instruction and the opportunity to engage directly with IRRI’s scientists and the research environment. Many shared that the training provided valuable knowledge they could apply immediately in their respective research institutions.

Looking ahead, IRRI aims to offer the Hybrid Rice Breeding Training Course again in 2026, continuing its commitment to supporting research and innovation in hybrid rice development.

Interested in designing a course for your organization? Email us at education@irri.org

Uzbekistan Researchers Complete Hands-On Training on Hybrid Rice at IRRI

Two researchers from the Rice Research Institute of Uzbekistan completed a 3.5-month on-the-job training program on hybrid rice technology at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) headquarters in Los Baños, Philippines. The training, held from August 25 to December 7, 2024, aimed to build technical expertise in hybrid rice breeding, seed production, and cultivation to support Uzbekistan’s agricultural modernization and climate resilience goals.

Facilitated by IRRI Education in collaboration with the Rice Breeding Innovation Department, the training was designed to provide an in-depth, hands-on experience. The first month focused on hybrid rice breeding, including floral biology, hybridization techniques, and field visits. Sessions on seed production practices such as transplanting of A, B, and R lines, GA₃ application, and pollination methods, followed this. From October to December 2024, the researchers concentrated on hybrid rice cultivation and were exposed to performance trials, socio-economic impacts, and improved cultivation strategies.

Facilitated by IRRI Education in collaboration with the Rice Breeding Innovation Department, the training was designed to provide an in-depth, hands-on experience. The first month focused on hybrid rice breeding, including floral biology, hybridization techniques, and field visits. Sessions on seed production practices such as transplanting of A, B, and R lines, GA₃ application, and pollination methods, followed this. From October to December 2024, the researchers concentrated on hybrid rice cultivation and were exposed to performance trials, socio-economic impacts, and improved cultivation strategies.

The program included full logistical support, from airport transfers and accommodation at IRRI Residences to visa assistance and insurance coverage, ensuring a seamless learning experience. A structured orientation, regular monitoring, and a post-training evaluation rounded out the training journey.

This activity forms part of IRRI’s ongoing commitment to strengthening the capacity of partner countries and advancing science-based solutions for sustainable rice production. (Click this link to learn more about the program)

Interested in designing a course for your organization? Email us at education@irri.org